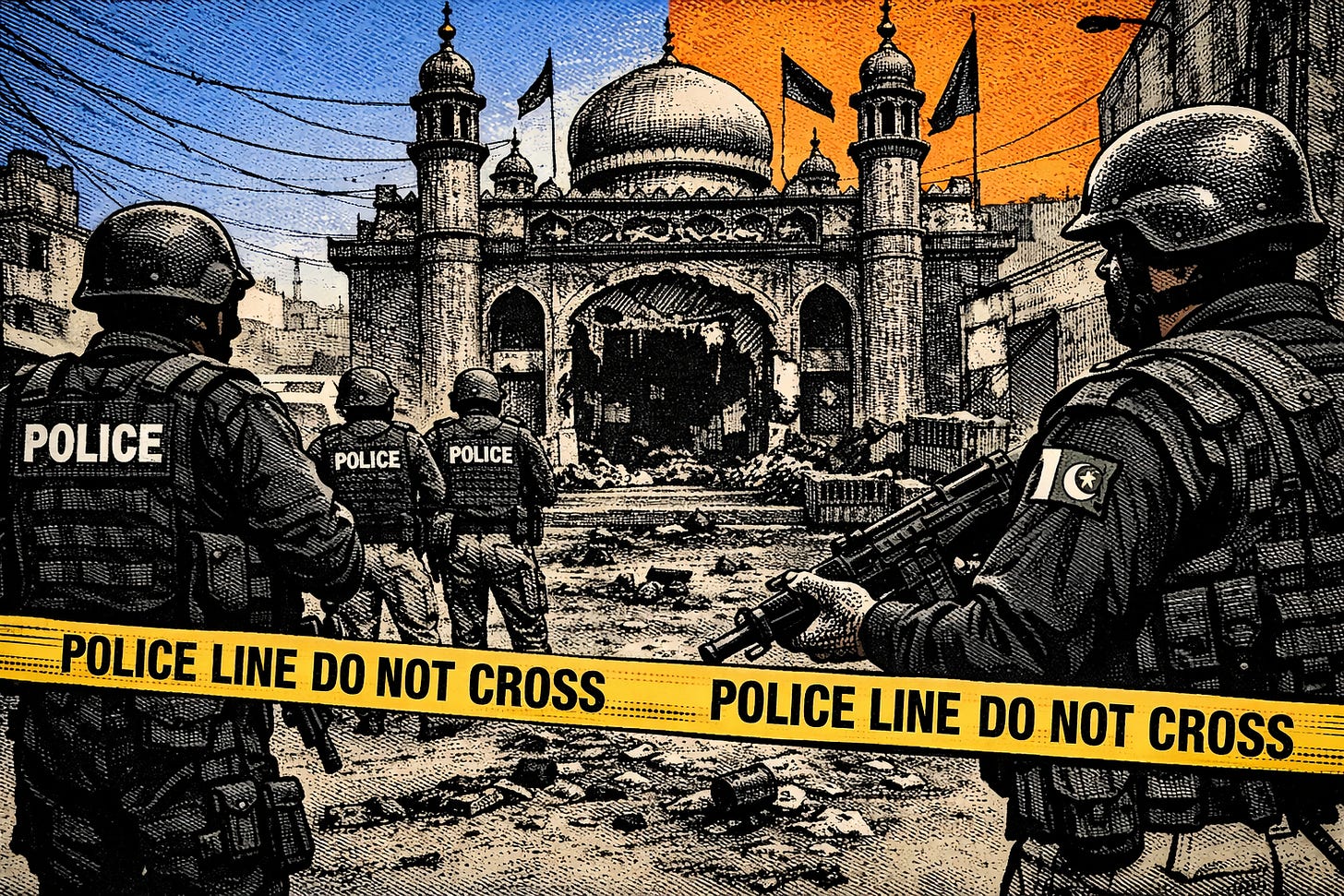

How do you bomb a mosque in a security state?

Pakistan’s security establishment insists it is winning.

According to the NYT, “In recent years, Pakistan has arrested, jailed, or killed dozens of Islamic State militants along its border with Afghanistan.”

A state that announces body counts as proof of competence invites one obvious question. If this is success, why did a suicide bomber walk into an Imambargah (a Shia mosque) near the capital during Friday prayers and kill 31 people while wounding 169 others?

And when the time comes to accept responsibility, the state-paid apologists resort to calling terrorist organizations that openly exist in the country “so evanescent.”

This is the vocabulary of abdication.

Pakistan’s military does not describe political dissidents, journalists, or protesters as “evanescent.” Those people are found quickly. And their phones are tapped, homes are raided, and movements are tracked. But when Shia worshippers are blown apart, the enemy suddenly becomes mist.

Islamabad is the most surveilled city in the country. It is layered with checkpoints, barricades, and armed patrols. Yet even these are revealed as theater.

“These barriers and checkpoints give a sense of security, but they don’t do much.”

The quote does not come from an activist or a grieving family member. It comes from Ihsan Ghani, a former top counterterrorism official. When the people who built the system say it is cosmetic, you don’t have to dig further to identify the culprit.

Then comes the quiet confession that explains everything.

“There’s no cooperation among different Pakistani institutions on this issue.”

Oh, so it’s a coordination glitch? How convenient.

Pakistan is a country where the military dominates every major institution, either directly or indirectly. If there is no cooperation, it is because the military does not care enough to enforce it.

Fragmentation here is the feature, not a bug. The same military that prides itself on discipline and hierarchy somehow cannot align its own security wings when Shia lives are on the line?

The state also cannot claim ignorance.

The bomber is identified as a Pakistani citizen who “had gone to Afghanistan several times in recent months.”

Several times. Across one of the most militarized borders in the world. Make it, make sense.

After years of claiming total vigilance, Afghanistan and Pakistan then perform their ritual blame exchange, accusing each other of harboring militants.

ISIS-K “has maintained strongholds in the border areas of both countries” and is estimated to have “about 2,000 active fighters.”

That number is not new. What is new is where the bombs land. They only seem to land in Shia mosques. They land where the state claims control is strongest. They land to kill minorities.

The sectarian dimension is acknowledged and then quickly buried. The attack “has also threatened to revive sectarian tensions.”

Threatened? As if sectarian violence were dormant by accident rather than managed through selective enforcement and selective blindness.

A Shia political leader calls the bombing “a grave failure to protect human lives.” Even that phrasing is restrained. The failure is not abstract. The lives were marked as expendable long before the vest detonated. It’s the minority, stupid.

And then we have the military’s economy. Oh, so fragile.

The bombing “threatens to undermine Pakistan’s efforts to revive its moribund economy by attracting foreign investment.”

We are reassured that a massacre “doesn’t change” the fundamentals of a military state’s economy. However, it “might change whether a U.S. delegation is going to travel to Islamabad to hear their pitch.”

This is the hierarchy laid bare.

The danger is not that Shias can’t pray safely in the capital. The danger is that investors might hesitate to board a plane.

Taken together, these quotes form a complete indictment.

The military claims success while admitting insecurity. It explains violence as elusive while policing everything else with ruthless efficiency. It acknowledges institutional dysfunction without correcting it. It mourns sectarian deaths while preserving the conditions that make them routine. And it laments the economic consequences and damage to its global reputation.

Nothing here suggests surprise. Everything suggests maintenance. It’s like everything is going according to plan.